by Paul Ejime

More than 50 years after its formation, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) ought to be in a celebratory mood as arguably the best-performing Regional Economic Community (REC) in Africa.

However, the regional economic bloc, once internationally lauded for its outstanding achievements, especially in preventive diplomacy, conflict management and control, now faces a devastating crisis of legitimacy, confidence and poor leadership at national, regional and institutional levels, with the risk of avoidable disintegration.

A decade after its formation, crippling governance challenges underpinned by conflicts and security threats meant that the organisation’s most notable achievement was the ECOWAS Free Movement Protocol adopted in 1979, which made it the first region in Africa to introduce a visa-free regime across national boundaries, and the right of settlement for citizens in any member State.

The institutional/reputation haemorrhage has been gradual but telling and consequential.

Set up on 28th of May 1975, through the Treaty of Lagos as “a transnational framework for economic cooperation and sociocultural exchanges, with a view to eventual unity of the nations of West Africa,” ECOWAS has evolved and unravelled from a zone of authoritarian regimes and military dictatorships in the 1970s/80s to an assemblage of member States, which embraced multiparty democracy of various shades until 2020.

The membership had increased from 15 to 16 nations before Mauritania withdrew in 2000. Yet, by 2025, the membership declined to 12 after military juntas withdrew Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger from ECOWAS to form the so-called Alliance of Sahel States, AES. Two other member States, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau, are under suspension.

General Mamady Doumbouya, who seized power in Guinea in a September 2021 military coup, has transmuted to a civilian president after an election with no credible opposition. Guinea looks set to be readmitted by ECOWAS, even though Doumbouya has violated Article 1(e) of the 2001 ECOWAS Supplementary Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance, stipulating that “no serving member of the armed forces may seek to run for elective political.”

Doumbouya achieved his political ambition through a controversial constitutional amendment and referendum. But he is not alone in the “unconstitutional change of government.” Junta leaders and elected civilians have perfected “constitutional and electoral coups” in Africa.

From President Alassane Ouattara of Cote d’Ivoire in 2016, to deposed Alpha Conde of Guinea, who forced through a constitutional change in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic; Presidents Faure Gnassingbe of Togo in 2023, and Patrice Talon of Benin, in 2025, the method is similar.

Ouattara, 81, recently won a fourth term in an election with no strong opposition, after he had repeatedly said he wanted to give younger candidates a chance.

Conde’s third-term bid ended in his fall with the Doumbouya-led coup. Faure and Talon have generally escaped without consequences after violating ECOWAS rules, particularly Article 2(1) of the 2001 Supplementary Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance against “substantial modification… of electoral laws in the last six (6) months before the elections…”

Faure seized power after the death of his father, Gnassingbe Eyadema in 2005 and claimed victories in subsequent disputed elections. He changed the constitution a month before the April 2023 controversial legislative polls to change Togo to a parliamentary system.

With the changes, parliament will elect a symbolic President of the Republic, while a powerful President of the Council of Ministers conducts the nation’s policy and leads the parliamentary majority.

Talon has announced he will not seek a third-term in the April 2026 poll, but is believed to be supporting his finance minister, Romuald Wadagni, as his successor.

Like many of his colleagues in the region, Talon has been accused of authoritarianism, having emasculated the opposition. He has also extended the tenure of the President from five to seven years under a constitutional alteration that introduced a bicameral legislature with a Senate of appointed members, comprising former Presidents and others, including himself.

The tenure of the Senate head, which Talon is gunning for, will be unlimited.

While business tycoon Talon might have been shaken by the 7 December 2025 coup attempt, which Nigeria and France helped him to foil, the repressive and authoritarian machinery he introduced persists.

In The Gambia, Adama Barrow, an accidental candidate who won the 2016 presidential election after former dictator Yahya Jammeh had jailed the main opposition leaders, was inaugurated in Senegal because of political tension in his country.

The Barrow government has since jettisoned a draft constitution that cost the country millions of donor funds to produce and backtracked on promised political reforms. He is laser-focused on his third-term re-election in December 2026, using the same 1997 Constitution that was in effect during Jammeh’s 22-year ruthless regime.

As if these were not enough, on 26 November 2025, Umaro Sissoko Embalo, President of Guinea-Bissau, took the unconstitutional change of government to an absurd new level through a self-coup and handed power to his loyalists in the military.

In an apparent move to avoid defeat in the 23 November 2025 presidential election, having excluded viable opposition and dissolved the parliament twice, Embalo announced the dubious coup.

The head of his Presidential Guard, General Horta Inta-A is now the Transitional President, while Ilídio Vieira Té, his Campaign Director in the botched election, is the junta’s Prime Minister and Minister of Finance.

Defying ECOWAS, which has demanded a shorter transition, instead of demanding the release of the election results, the military regime has announced a 12-month transition programme, fixed elections for 6 December 2026 and unilaterally changed the national constitution, granting expanded powers to the President, unlike the previous system where the President and Prime Minister shared powers.

The controversial constitutional changes and other violations of regional texts and protocols by ECOWAS leaders have largely gone unchallenged by the ECOWAS Commission, “…comprising experienced professionals (charged with) providing the leadership to achieve the vision of the (ECOWAS) founding fathers…”

Over recent decades, the Commission has either failed to provide “quality advice/leadership” or its input has been dismissed/ignored by the ECOWAS Authority, the Supreme Institution, or both.

While the political leaders or the Authority should take the highest responsibility for ECOWAS’ drift towards disintegration due to their anti-democratic dispositions, such as the repression of opposition, state capture, human rights violation, decline of the rule of law, and the shrinking of civic space, resulting in the resurgence of military rule in the region, the technocrats at the Commission cannot be completely exonerated.

Military coups are an aberration, but are not the only form of unconstitutional change of government rejected by ECOWAS rules. When political leaders violate ECOWAS rules/protocols, the Commission is duty-bound to point out the breaches through various channels, including public statements; otherwise, it becomes complicit in the violations.

It is natural for leaders in breach to resist being called out. Therefore, as the Commission’s professionals/technocrats are accountable to the Community citizens and not the politicians, their commitment should be to deliver on the overarching objectives of the ECOWAS founding fathers.

The professionals should not be afraid of taking tough decisions or losing their jobs, but must prioritise their personal and corporate integrity of ECOWAS.

Two examples come to mind. In 2009, the ECOWAS Commission suspended Niger after then-President Mamadou Tandja went ahead with controversial parliamentary elections, and in 2011, the Commission boycotted elections conducted by President Jammeh because of the “repression and intimidation” of opposition and the electorate, among other reasons.

In contrast, after the junta has demanded the withdrawal of ECOWAS forces from Guinea-Bissau and shunned a regional military delegation, the estimated 500-strong ECOWAS Sustainability Support Mission (ESSMGB) are sitting ducks in that country with no clear directive from ECOWAS.

After his self-coup, Embalo continues to direct the junta regime from the background, with his portrait pictures still adorning government offices in Bissau.

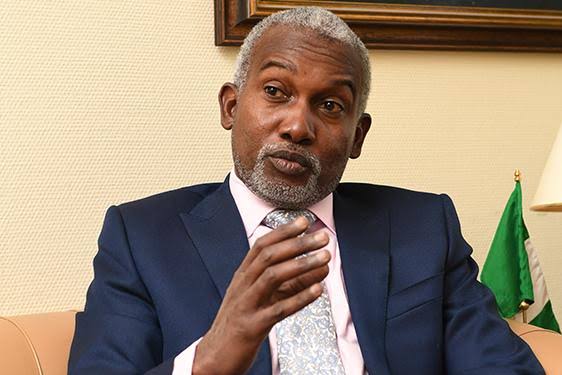

The Embalo-instigated crisis has left ECOWAS sharply divided. Recent talks between the Bissau junta and a delegation comprising Sierra Leone’s President Julius Maada Bio, the current chair of the ECOWAS Authority, the Senegalese President Diomaye Faye and the Commission President Omar Touray, were anything but positive.

The junta is digging in with Embalo’s main opponent, Fernando Dias, who claimed victory in the November election, still taking refuge in the Nigerian embassy in Bissau, while other opposition figures are either in detention or fled Guinea-Bissau, a “narco-state,” which has seen at least nine attempted and successful coups since independence from Portugal in 1974.

The transitional Charter, adopted shortly after the coup, bars the junta leaders, including General Inta-A, from running in the transition election.

However, the damage to ECOWAS’ reputation if violators of its own rules go scot-free or if Embalo should return to power after the self-coup will be difficult to imagine as Guinea-Bissau inches towards a civil war.

Also, critical questions will be raised about the legacy of the four-year mandate of the Touray-led Commission, which ends in June.

ECOWAS requires urgent redemption and reinvention, and Nigeria should step up as the regional hegemon. A lot will depend on how the organisation tackles the Guinea-Bissau and other simmering crises in member States, coupled with a drastic restructuring of the Commission.

*Ejime is a Global Affairs Analyst and Consultant on Peace & Security and Governance Communications

Leave a comment