A new University of Maryland study suggests that successive strains to the novel coronavirus are becoming more transmittable through the air.

Back in the early days of the pandemic, scientists couldn’t initially confirm that COVID-19 could be spread through particles in the air, and it was believed to be transmitted through actions such as coughing and sneezing.

Newer

variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, may become more airborne as they evolve, according to a recent study from the University of Maryland, published in the

Clinical Infectious Diseases journal last week.

People infected with the Alpha strain of COVID-19 are exhaling 43 to 100 times more of the virus into the air compared to those infected with the original COVID-19 strain.

The research found that the viral load in the air from Alpha variant patients was 18x more than could be explained by the increased amounts of virus in nasal swabs and saliva.

Researchers also found that face-coverings, such as surgical masks and cloths, reduce the amount of the virus breathed out into the air by about 50%.

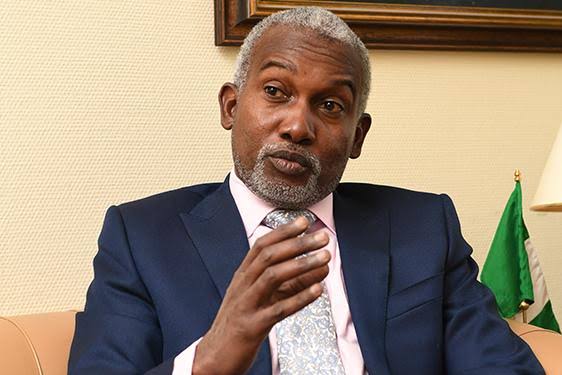

“Our latest study provides further evidence of the importance of airborne transmission,” said Dr. Don Milton, professor of environmental health at UMD’s School of Public Health. “We know that the Delta variant circulating now is even more contagious than the Alpha variant.”

Because research indicates successive variants keep getting better at traveling through the air, better ventilation and tight-fitting masks, in addition to vaccination, can help offset the increased risk, Milton said.

“Because research indicates successive variants keep getting better at traveling through the air, better ventilation and tight-fitting masks, in addition to vaccination, can help offset the increased risk,” he added.

“We already knew that virus in saliva and nasal swabs [were] increased in Alpha variant infections. Virus[es] from the nose and mouth might be transmitted by sprays of large droplets up close to an infected person. But, our study shows that the virus in exhaled aerosols is increasing even more,” said one of the study’s authors, doctoral student Jianyu Lai.

The researchers recommend a “layered approach” to protect people in public-facing jobs and indoor spaces — these include vaccinations, tight-fitting masks, improved ventilation, increased filtration, and UV air sanitation.

To test whether masks work in blocking the virus from being transmitted among people, the study measured how much SARS-CoV-2 is breathed into the air by the infected first without a mask, and then after putting on a cloth or surgical mask. The researchers found face coverings cut the amount by about 50%, but didn’t wholly stop infectious virus from getting into the air.

“The take-home messages from this paper are that the coronavirus can be in your exhaled breath (and) is getting better at being in your exhaled breath, and using a mask reduces the chance of you breathing it on others,” said Assistant Clinical Professor Jennifer German, a co-author of the study.

The team also included researchers from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Duke-NUS Medical School and Rice University.

Leave a comment