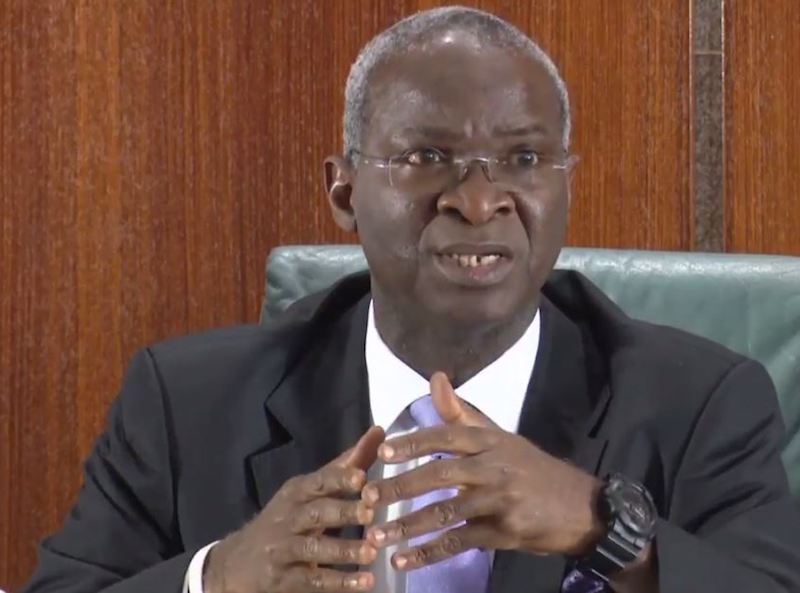

Abba Kyari was an unlikely svengali. The most prominent African victim so far of coronavirus, who has died at the age of 67, his appointment to one of the most influential positions in Nigeria, as the president’s closest adviser, took many seasoned politicians by surprise.

A lawyer by training and banker by profession, Kyari was also an outsider by nature, uncomfortable with the intrigues of political elites. Yet President Muhammadu Buhari knew what he was getting when he made his friend of more than 40 years his chief of staff, after an against-the-odds election victory in 2015: fierce loyalty, hard work and an attention to detail that often unsettled his opponents. Kyari’s abrupt death has left friends and rivals alike pondering how the self-effacing intellectual could have become so powerful in the past five years.

He leaves behind a vacuum in a time of uncertainty, with the price of oil, on which Nigeria depends for export earnings, in free fall, and the world beyond paralysed by the virus that took his life. Kyari was born in Bama, a town in Borno state that has been razed to the ground during the ongoing insurgency by Islamist extremists in Nigeria’s north-east. Although a Muslim, he attended a Christian missionary school before studying at Warwick and Cambridge universities in the UK in the 1980s. Starting as a journalist, he went on to become a banker, was chief executive of United Bank for Africa, one of Nigeria’s leading banks, and sat on the board of subsidiaries of both Unilever and ExxonMobil. An inveterate Anglophile, he counted Radio 4, Private Eye magazine, Martin Wolf’s columns in the Financial Times, and kippers among his favourite indulgences, and left-leaning thinkers, such as the economists Amartya Sen and Arthur Lewis, as enduring influences.

He was acutely aware of the dilapidated state, and limited capacity, of the public administration in Nigeria. Yet, his experience in business also made him wary of a private sector too often defined by a parasitic relationship with government. He was sceptical about liberal market solutions to Nigeria’s many problems, in the absence of the rule of law. That tension underlay much of his time in office, as he rebuffed advice, from the IMF among others, to curtail a controversial exchange rate regime. His friendship with the president went back to before the coup that first brought Mr Buhari to power in 1983, and he stood by the former general during three fruitless attempts to gain power at the ballot box, a passionate supporter of his anti-corruption agenda.

Often he would appear as Mr Buhari’s mouthpiece, finishing his sentences when interviews veered into areas in which he was less conversant. That was a role he carried into office when Mr Buhari finally unseated the incumbent president, pledging to root out graft, end conflict and diversify Nigeria’s economy away from oil. It was an agenda that quickly ran into obstacles. Recession, institutional resistance and Mr Buhari’s faltering health all took their toll. Throughout, Kyari acted as a gatekeeper to the president, shielding him from intrigue and dealmaking. Along the way he lost friends and ruffled feathers. His critics accused him of locking down the administration as the head of a cabal that exercised too much influence on key decisions and appointments. Yet even from the centre of power, Kyari would express exasperation at the institutional inertia and systemic corruption that held up change.

“He wanted to protect the president and to take time to understand all the terrible things that had been going on,” said a former official who worked with him. History would be kinder to Kyari than his contemporaries, the official added, and credit him with playing a crucial firefighting role from behind the scenes. “People were saying we would end up like Venezuela.

It wasn’t perfect, but we didn’t.” Increasingly Kyari focused his energies on a few priorities: agricultural reform and efforts to revive a moribund power sector and transport infrastructure, symbolised by the construction of the first new bridge in a generation to span the river Niger. He was close to launching long-delayed initiatives to restructure the notoriously underperforming oil and gas sector. Nigeria has a long history of frustrating and diverting those who most want to bring change. Kyari’s own efforts have been cut short, just as he had manoeuvred himself into a position where he could have had greater impact.

Against medical advice, many officials trooped to attend his burial. They have been told to stay away from the president since. The virus that took Kyari’s life has temporarily taken on his role as gatekeeper.

Leave a comment